One of my children and their partner have changed their names in the last few years. On the face of it, this does not present me with any problems, and I am happy that they are re-defining themselves in new and positive ways. This week, however, I have been reflecting on the historical significance of formal names.

Because of the name changes and because I have moved to a different province in Canada, I am in the process of updating my will. My children are my primary beneficiaries and their partners are named as next-of-kin in the event that one of my children pre-deceases me. The assumption is that my children will live longer than me and thus be responsible if I become physically or mentally incompetent. That assumption includes their willingness to take over responsibility for my health, my property, and my finances. Now, all of this has got me thinking about names, and formal legal names in particular.

When we choose a given name for a child, we select from names that are within our family’s traditions, names that are in vogue, and names that have positive connotations. I chose names for my children that were, I thought, fairly normal and traditional within the Anglo-Saxon British world that I came from. I didn’t realize the extent to which those names would be generationally-specific, but I still like the names I chose.

More to the point, though, is that they have inherited the last name that they were given by their father. This is the thought I am mulling over today.

I have been married twice and both times I took the last name of the man I married. There was no question about it. That is simply the way it way it was, and the way it still is to a large extent. I, and probably you, live in a patriarchal society. Inheritance is tied up with the identity of the male and his property.

That is all well and good if the male who provides his name is open and generous with his offspring, but if the marriage ends, all the goodwill sometimes goes away. What is left is the name.

I recently posted a comment on a Facebook page related to the town where I grew up. I mentioned the schools that I attended and identified my “family” name. I gave the name my parents had, my childhood name, my maiden name. It was not the name I have lived with for the last fifty years. It was not the name my children have.

Don’t get me wrong. I love being associated with my late husband’s siblings and extended family. They are wonderful people and I enjoy their company whenever we are together. I am pleased to call them relatives. But, their name is my name only by marriage. It isn’t my family name, exactly.

All of this has me thinking about patriarchy and its long reach. I wonder if I would have a different name if I lived in a matriarchy. I think about how marriage conveys so much more than a name if there are children. I feel concern for the children who are conceived outside a marriage, without “a name”.

If you have “a name,” you are legitimate. If you don’t, you may struggle to survive. If you are the offspring of a famous billionaire who sometimes gives his name to his children and sometimes does not, you have no control over that. It’s up to him. He is the father and it is a patriarchy. There is not much you can do.

But, you can change your name. It is time-consuming and bureaucratic, but it can be done. As my child and their partner have shown me, this is not as immutable as I previously thought. Names are what you make them, and you can make them in your own image.

What is in a name is entirely up to you. I choose to associate my family name with my birth parents and my siblings. My married name is associated with a good man and his lovely sisters. If I could have both of those names at once, it would feel right. But, our laws don’t easily allow for that, so I will leave both those names at the back of my mind along with all the good people whose thoughts they conjure up.

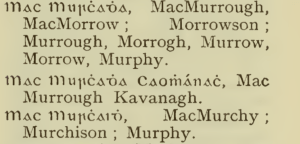

I changed to my maiden name after my last divorce. It’s the name I most identify with. I don’t think of it as my father’s name so much. Since my brother changed the spelling of our name to MacLeod, I’m the only McLeod left. Yes, I don’t see much change in our patriarchal system.

I’m intrigued that your brother changed the spelling of the family name. You probably still have to spell it out for people either way.

Doug went to Australia in his youth, but he may have changed it earlier. I’m positive my father never knew. They did not get along, to put it mildly. HIs kids argued that I had changed it., but I had a photo of my dad’s tombstone.

All my life I have had to spell out my name, sometimes even my first name.

It is a lot to ponder. I hyphenated my last name with my first marriage. I was struggling with the name change representing a change in who “owned” me. But hyphenating was a bunch of explaining, and a bunch of spelling it out to people. When that marriage ended, I reverted back to my birth name, with relief. Not that I my family of origin is all that venerable, sorry to say. But I like the alliteration of Lorna Larson. And that my first name contains all of the letters, except “s” of my last name. Where I live, folks struggle enough with my first name, so having an easy last name is helpful.

My young adult stepchild changed their name with their gender last year, and that has been an easy adjustment for me.

My nine-year-old grandchild has requested a name change (not gender-related) and my daughter and sil are honoring it. It’s taking me longer to adjust. Now I’m getting confused about my grandchild’s pronouns, having evidently linked name-change to gender change. I’ll catch up, I’m sure!

It is a lot to ponder, isn’t it! Having been through some similar personal and family name changes, I can only empathize with your adjustment process. I still sometimes get the pronouns wrong, despite all my best intentions. Thankfully, my family members are very forgiving of my shortcomings.

Yes, I appreciate those understanding family members, too!